Social Manufacturing

The global connection of local stakeholders with a size that is proportionate to their own territory is a step forward in the fulfillment of digitalization.

by Marco Mari

20th September 2020

Remember what the future looked like before this pandemic? We were discussing about climate change, trade wars, data protection linked to the tech economy, the seemingly unrelenting rise of cities.

As a society, we were increasingly keen on seizing the opportunities and manage the risks of the Great Acceleration, characterized by a constant and unstoppable growth of human activity including demographic expansion, production of wealth, surge in travel and connectivity, as well as the progressive erosion of the soil and the ongoing depletion of natural resources.

Faced with this increasingly manifest global dynamics, people and organizations around the world became more aware of the dangers and more worried about the consequences of such a system, thus engaging in activism to push for a more responsible economy, an economy that is more respectful of the balance with the ecosystem we live in. And then the pandemic happened, putting us all in a lockdown. In a matter of weeks, one nation after another, as if powerless, rapidly went from a great acceleration to a great suspension. And now, not without struggle and in a disjointed fashion, without having had the time to truly ponder on how we got here, we are witnessing reopening and reboots, with some missteps, as well as attempts at radically transforming our social structures.

Everything will be fine, but nothing will be the same. How many times have we heard these words? And yet we keep eluding the most simple and fundamental question: where are we going?

A couple of months ago, in the belief that globalization will not draw to a close but will rather be transformed, we hosted a conversation on the future of global value chains with Bill Emmott, Federico Fubini and Diego Piacentini.

Continuing this investigation, and discussing about it with managers and entrepreneurs, we came across a term we had heard little about for quite some time: Social Manufacturing.

conversations.

A conversation with Diego Piacentini, Bill Emmott and Federico Fubini.

Social Manufacturing: a new definition

Once associated with the collaboration between companies and individuals, mainly linked to the advent of additive manufacturing and the potential of 3D printing, Social Manufacturing could hold a new meaning in the post-Covid era. In manufacturing economies, Social Manufacturing could stand for the end of the primacy of economies of scale, in favour of the emergence of micro-economies and micro-policies that are globally connected and intertwined.

While this may look like a return to the past, this shift could actually be the true fulfillment of digitalization and globalization.

As much as it may seem contradictory at a first glance, the global connection of local stakeholders with a size that is proportionate to their own territory is a step forward in the fulfillment of digitalization. For years, possibly influenced by the embedded notion of mega factories and large-scale productions, the tech and service economy developed as a predominantly urban phenomenon, where everything happens in large centralized and where the density of the assembly line is rendered in large open spaces filled with modern workstations and rest areas.

To the left: workstation inside an AI start-up. To the right: workstation inside a clothing factory.

Now that the media show these empty campuses, voided of their typical energy, it is perhaps easier to spot the similarities between the mill towns, where the housing, canteens and after-work facilities had been built very close to the factory floor, with the campus-cities, where despite the dematerialization of work there has been a relentless centralization driven by new economies of scale. The old factory floor is now the wide open-space, and the computer is the old loom or lathe.

Full digitalization and globalization can instead lead to a full decentralization, enabling growth not in terms of scale but in terms of extensiveness and reach and, more importantly, transforming value chains into value networks, resulting in a more direct, transparent and equitable attribution of the value created from the very beginning.

In a connected system of micro-economies and micro-policies, relationships will become central in the production and distribution processes. Does this imply the return of a relationship capitalism, with its information asymmetries and opaque decision making?

Not necessarily. Not if we are able to develop new concepts of proximity, to guarantee transparency impartially by leveraging the potential of information technology, and to build on the positive features of close relationships, such as solidarity and social responsibility. Not if we are able to think of competition as a way for companies and organization to shape together the evolution of their industry, rather than simply creating and defending individual competitive advantages.

Decentralization as outcome of full digitalization and globalization

Two key factors will determine whether this transformation will result in a real progress: how we will develop the new technological infrastructures needed to transform value chains into value networks, and how we will give consistency to the direct and transparent dialogue between individuals and organizations.

Focusing on manufacturing, we see two interesting opportunities: the growth of open information systems that can support a new production and supply chain management, and the emergence of a regenerative economy in place of a consumption economy.

The possibilities offered by information systems, that is the chance to integrate more easily multiple solutions for raw materials supply, logistics or production, enable a radical innovation of business organizations.

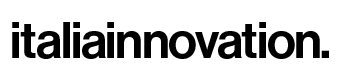

For example, thanks to the so-called headless systems, it is possible for customers to purchase products that sit in different warehouses and are sold by different companies through a unique interface which allows for an integrated user experience. So instead of relying on yet another digital retailer with huge distribution centers, quality artisans and small or medium sized producers will be able to collaborate, reach a critical mass and access new markets through the leverage of technology. In this endeavour, it is worth monitoring what some Italian start-ups are doing, such as Commerce Layer and Dato CMS, as well as understanding how these new technological platforms will be able to leverage new quality and sustainability certification tools such as blockchain solutions like the ones proposed by IBM with its Food Trust, or on a smaller scale by start-ups like Provenance.

Farmer Connect is a project powered by Sucafina, global green coffee trader, and the IBM Food Trust.

Much like what is happening in the information economy, manufacturers will experience a sharp increase in the range of choices thanks to the greater variety and distribution of sources and resources. At the same time, it will become increasingly important to adopt metrics and certifications that can actually guarantee superior quality and sustainability standards.

Beyond consumerism: quality is sustainability

To understand the meaning behind these seemingly vague notions of quality and sustainability, we can offer the experience and the content framework developed over the past three years by Italia Innovation with its innovation programs, particularly in the ones led by Riccardo Illy on Disruptive Quality. What distinguishes disruptive quality productions is the selection of the best raw materials available without any compromise, the use of low impact industrial transformation processes, designed to enhance the quality of the raw materials instead of to eliminate their defects, the incompatibility of this production process with that of mass productions and a process and final product deeply rooted in social and environmental sustainability, and a clear perception of excellence even by non-experts.

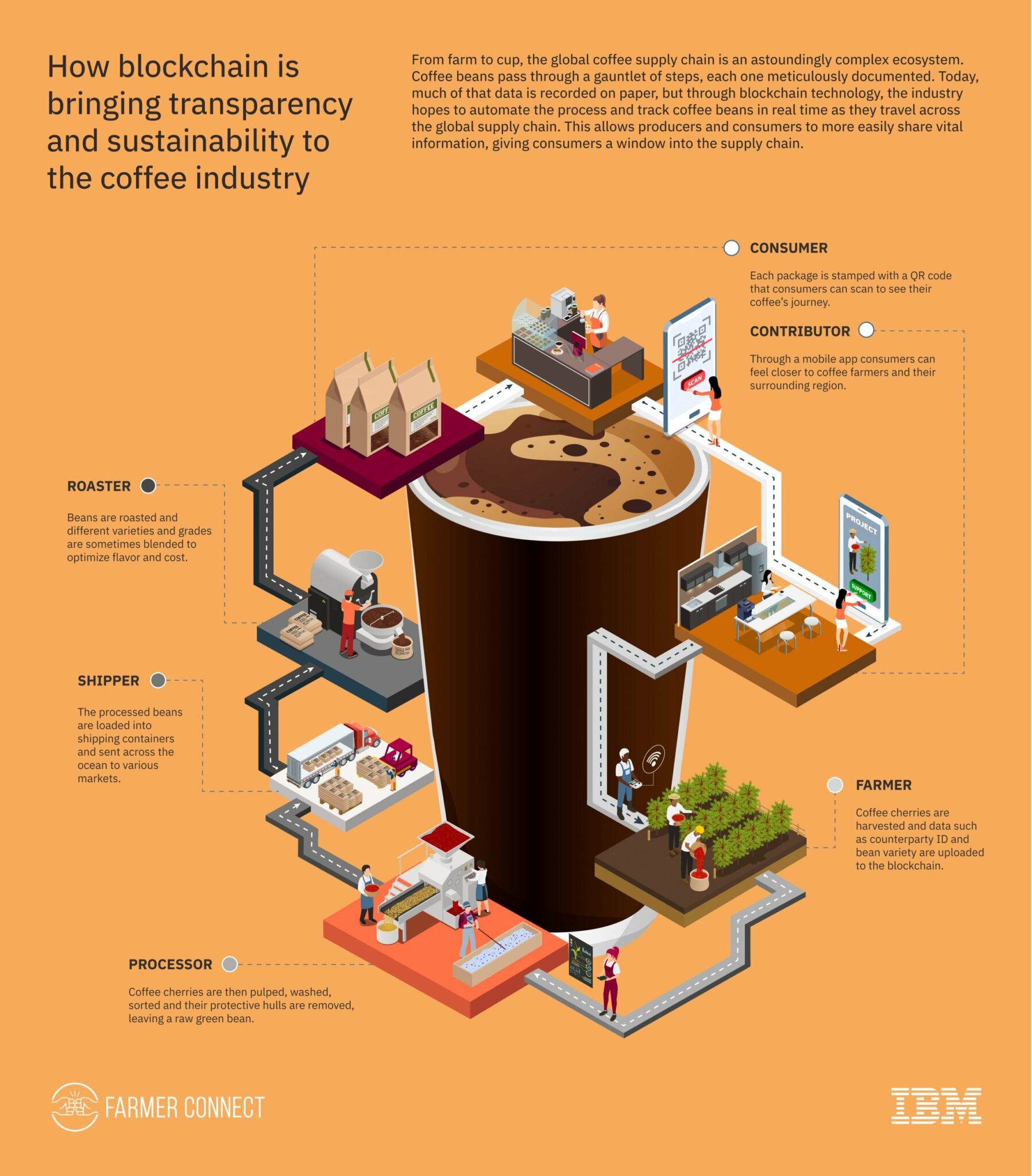

This new production paradigm, in which quality becomes the guiding principle for supply and production chains as well as cornerstone for sustainability, can help in the transition from a consumption-based economy and society to truly regenerative economies. To this end, holistic certifications such as the Regenerative Organic Agriculture Certification can serve as common ground for producers and stakeholders who share this approach, setting them apart from what will soon definitively become the old way of doing business.

The Regenerative Organic Agriculture Certification was created in 2017 by a group of pioneers in the fields of business, agriculture and science, with an holistic approach and with the goal of defining the highest standards in terms of quality and sustainability for soil health, animal welfare as well as social responsibility towards workers and communities involved in production activities.

The Regenerative Organic Agriculture certification process, as defined by the Alliance.

Building on the work of certifications on organic productions as well as on social impact like fair trade, B-Corps and more, the Regenerative Organic Agriculture Certification offers the opportunity to involve the entire supply chains or networks in a process of transparency and continuous quality improvement, with measurable benefits not only for the agri-food sector but for all sectors which rely on the relationship with nature, including the textile and furniture, to name a few.

The future of Social Manufacturing will unfold through a combination of new technology and new processes, making it possible for small stakeholders who are pursuing excellence in their industries to take part in global value networks unleashing the potential of digitalization, and finally evolving the old consumer society into a society of sustained regeneration of value.